The Main Men

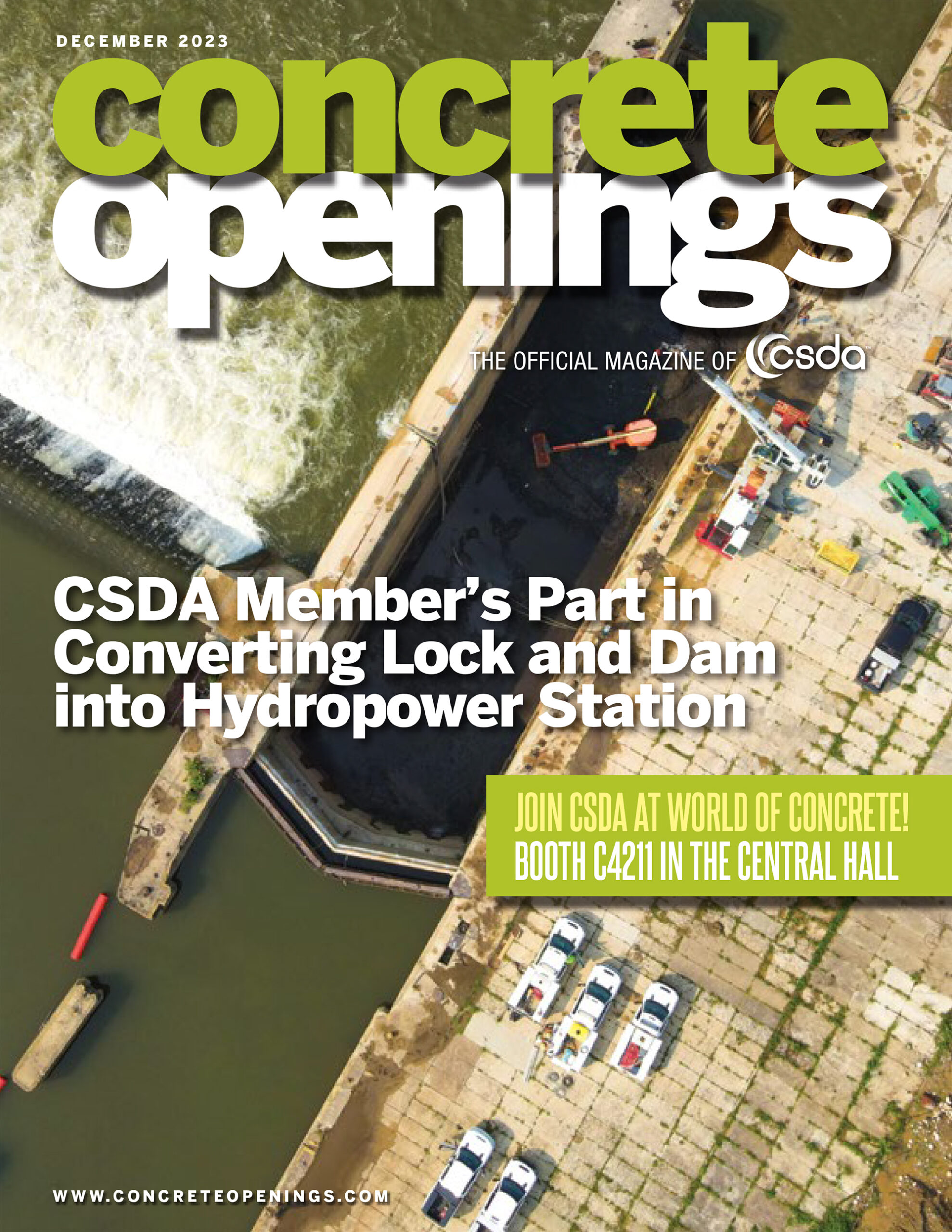

Header photo: Copyright, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2017, all rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Bridge Design Oversight Corrected by Wire Sawing Professionals

A 107-year-old road bridge in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was demolished early 2016 after the completion of a $65-million replacement project. The new 1,600-foot-long steel structure had been open to traffic for several months before an oversight in the bridge design was identified and needed immediate attention.

The new multi-girder Hulton Bridge has been built just upstream of the original structure. It has four 11-foot-wide traffic lanes (two in each direction), one 4-foot-wide median, a 4-foot-wide shoulder on each side of the roadway and a 5-foot-wide ADA-compliant sidewalk on the bridge’s southern side. The overall replacement project included realignment and reconstruction of nearby roads, relocation of utilities, drainage, pavement markings and improvements to intersections, lighting, traffic signals, curbs and sidewalks. Furthermore, six buildings on one side of the Allegheny River were demolished to facilitate construction. The entire project, including implosion of the original bridge, was completed in spring 2016 in time for the U.S. Open golf tournament at nearby Oakmont Country Club.

A section of a 12-inch-diameter gas main had been encased in concrete.

Deep within one of the bridge’s diaphragm sections, lengths of a 12-inch-diameter gas main had been encased in thick, reinforced concrete and passed through steel beams as the new construction developed. Unfortunately, the design plans for the structure had overlooked a requirement that the gas main have at least 6 inches of clearance around it for inspections, any potential repairs and to accommodate the expansion and contraction of the concrete during seasonal changes in temperature. The diaphragm had been designed to move with the expansion and contraction of the bridge throughout the year, as these changes would lead to several inches of movement between the diaphragm and the backwall. With only 1 inch of spacing between the gas main and concrete, it was clear that the gas supply would be compromised as this movement progressed.

A major concern was that the gas supply would have to be completely shut off in order to cut and remove the entire section of concrete-encased pipe and replace it—a costly exercise. However, a local CSDA member offered a quicker, safer and more cost-effective alternative.

“When we were first called to review the project, the new bridge had already been built and opened to vehicular traffic with the old bridge demolished,” said Dan Matesic of Matcon Diamond, Inc. in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “During construction, the general contractor followed plans that were later determined to have omitted a requirement for future gas line inspections and repairs. Following consultation with Brayman Construction Corporation, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (DOT) and the gas company, we devised a plan to wire saw and create a 24-inch by 24-inch box around the gas main, which ran through a 42-inch-thick concrete encased steel diaphragm section—perpendicularly penetrating through the beam. This work could only have been done using diamond cutting or drilling methods.”

The general contractor had placed the steel beam portion of the diaphragm, cutting a hole for the gas line to be pass through. Next, the gas company moved its existing 12-inch-diameter main from its original position at the old bridge to the new one. Here the main passed through the web portion of the diaphragm to traverse across the underside of the bridge, providing service to the neighboring town. The web of the beam at the gas line location was reinforced with concrete forms and matting before the entire structure, including the gas main, were encased in concrete as per the plans.

It was at this stage the general contractor realized that tolerances around the pipe had not been indicated, nor was possible to gain clarification prior to concrete placement. It was decided that a 0.5-inch-thick bond breaker would be wrapped around the gas main, to provide some spacing between the main and the concrete, and the work continued. Following a post-construction inspection and review of utilities, the gas company raised the issue that the newly replaced gas main did not comply with their inspection requirements for this type of structure. By specification, a 6-inch minimum clearance must be maintained for any gas main not earth embedded. Furthermore, there was not enough room around the pipe to accommodate seasonal shifts of the bridge structure as temperatures rose and fell.

“When we first viewed the site in the summer, the gap between the concrete diaphragm and the adjacent abutment was approximately 3 inches. By December, when it was around 40 degrees colder, the deck had contracted and the gap had increased to approximately 9 inches,” explained Matesic.

The contractor used wire sawing techniques to create a 24-inch square, 42-inch-deep “box” around the gas main.

The gas company, Equitable Gas, and the DOT consistently stressed to Matcon that any type of demolition or sawing activity could not pierce or penetrate its main. Collectively, an agreement was reached to use diamond methods that would only run parallel to the pipe. Additionally, it was understood that while some portion of chipping or breaking would be required, the relief cuts made by the cutting contractor would mitigate a lot of this work.

The wire sawing plan was a two-step process. First, four 0.625-inch-diameter holes were core drilled 42 inches deep at marked corner locations around the pipe for wire access, using a motor and bits from Diamond Products. A 20-foot length of diamond wire from K2 Diamond was run from one hole to another, which allowed Matcon to make a series of four pull cuts 24 inches long and 42 inches deep from the backside of the diaphragm section to the front. Each pull cut took around four hours to complete utilizing a hydraulic wire saw from Husqvarna Construction Products. Once the wire sawing was complete, the general contractor employed equipment to incrementally break and extract the cut piece away from the pipe.

“From the onset, we were substantially limited by the Department of Transportation’s bridge engineering team regarding the “footprint” of the cutting work. The diaphragm cut was the final load-transitioning piece for the structural beams carrying the new bridge. While provisions had been made to allow the gas line to pass through the structure, the opening we presented had to be minimized to the absolute smallest possible area. Its fabrication had to have negligible structural impact to the bridge while providing adequate inspection capabilities for the gas company and room for the concrete to expand and contract without compromising the pipe,” explained Matesic. “The gas company did shut off the gas supply and vacate the line during work operations, but the shut off was limited to the simple turning of a valve.”

By making four pull cuts with the wire saw, the contractor left a smooth finish while producing minimal vibration.

Further complicating the scenario, the gas main only turned to run parallel with the bridge after it exited the diaphragm. Running through the backwall and the diaphragm, it was oriented 10 degrees from perpendicular and Matcon quickly recognized this as a potential extraction issue. Wire sawing the piece with the pipe centered on one face would have resulted in the pipe being off center on the opposing side of the diaphragm. It was therefore decided that the wire access holes be made at compound angles. This ensured that when the cuts were completed the piece would not only pull from the hole without binding, but also enable extraction without any impact to the pipe itself.

Due to the nature of this project, the cutting contractor’s work was completed on a time and material basis. Matcon’s overall working time on the project was four 10-hour shifts.

“We were completely satisfied with the outcome. As the adage, “necessity is the mother of all invention” holds true, the issues presented by this scenario glaringly pointed to one profession in the construction industry—diamond cutting. We were proud to have had the opportunity to do this work,” concluded Matesic.

Company Profile

A CSDA member since 1985, Matcon Diamond, Inc. has been in business for 32 years. The company is based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, employs up to 75 operators and laborers and has a fleet of 50 trucks. Matcon offers concrete cutting services of slab sawing, wall sawing, hand sawing, wire sawing, core drilling and joint sealing.

Resources

General Contractors:

Brayman Construction Corporation

Sawing and Drilling Contractor:

Matcon Diamond, Inc.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Phone: 412-481-0280

Email: matcon@matcondiamond.com

Website: www.matcondiamond.com

Methods Used: Wire Sawing, Core Drilling